All we knew about the man named Michael J. Nevins was this: he was my great-grandmother Elizabeth’s father. His name was found in a family Bible but there was nothing else to tell us about him.

Just 13 years old in 1898, Elizabeth’s mother Ellen O. Taylor, (a native of Kent, England) arrived with her parents and sister in Boston where they made a home in Methuen, Massachusetts. By the time she was 20, Ellen gave birth to Elizabeth Nevins on February 23, 1906.

The story was that Ellen and Michael were married, but by 1910 Ellen had a new relationship. She married Peter Beeley (also an English immigrant) and together they would go on to have nine children together and be known as “Ma” and “Pa” Beeley. Michael seemed to vanish from the family history in a mere four years. So what happened to him?

Peter & Ellen Beeley, with Ellen’s daughter Elizabeth Nevins in 1910, Methuen, Mass.

For years the children assumed their older sister, Elizabeth was their full blood sister. One of the Beeley brothers remembers a young man coming around their house and asking him, “Is Elizabeth your sister?” To which the Beeley brother replied, “Yes.” “Well she’s my sister, too.” At the time, the family seemed content to leave the questions and their answers a mystery. The only reason Elizabeth even discovered she was not a Beeley as she grew up was because she found her birth record with the name Nevins in a cedar chest and confronted her mother about it.

My grandma, the granddaughter of “Ma Beeley”, had only ever been told—perhaps directly or indirectly—there was a divorce between Ellen and Michael Nevins. To her knowledge the family assumed he left them, but with Peter Beeley entering the picture so soon after their separation, and the stigma attached to divorce at the turn of the 20th century, it was not a topic of discussion. The common and legitimate reasons for divorce in that time were the big ones: adultery, abuse, desertion, or mental illness. It wasn’t until the mid 1970s could you file for a “no-fault” divorce in Massachusetts. It seemed a rather rare and scandalous story to me.

A few weeks ago my grandpa (he’s the one who drew me into this addictive hobby when I was in grade school) had some papers to give me from the Beeley cousins and from his own research. There were family trees of the Beeleys and one of a possible Nevins link. Mismatched census records and question marks showed me there was no evidence to support it was accurate. There seemed to be a few Michael Nevins floating around the Methuen/Lawrence, Mass. area in the early 1900s from census records, but to find out which Michael was “our” Michael, we needed more. However, Grandpa came across the birth record for Elizabeth Nevins. Studying this record was the first piece of the puzzle to confirm. We worked our way backwards.

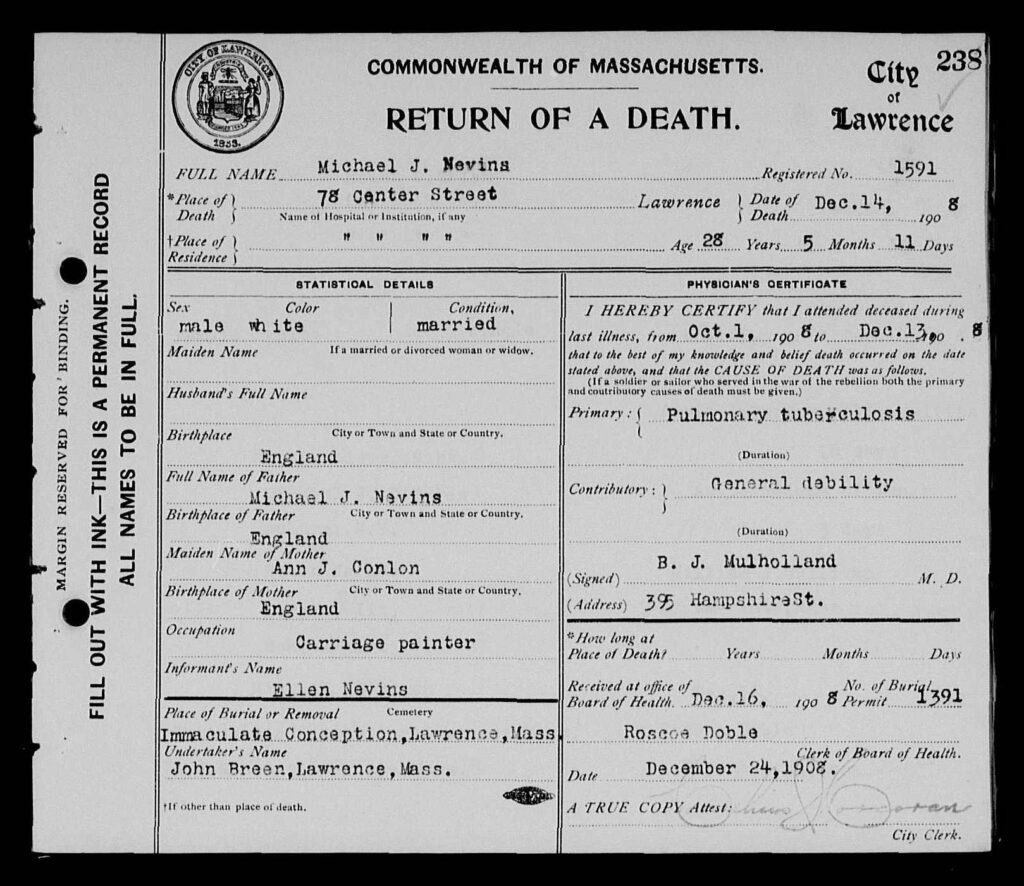

From his local genealogical society he was a part of, Grandpa told me about the site familysearch.org, and since he didn’t have the internet at home and I did, I entered a few variations of Nevins names. Finding a divorce record would be revealing and confirmation of the family story. Yet the search result that caught my eye was not a divorce record, but a death certificate.

What I was seeing would change the family’s narrative of Michael Nevins’ absence. I was so excited to tell my grandparents that grandma’s biological grandfather and grandmother didn’t divorce, they were separated by death. Sadly, with a young wife and a two-year-old little girl, Michael became ill with consumption (tuberculosis) and died. He was only 28.

So all these years family may or may not have had negative thoughts about this man who must have wronged Ellen in some way and was never heard from again. A legacy that was all wrong because of a life cut short. But it’s so odd—why say they divorced? Where did that version of the story originate? With Ellen before she met Peter Beeley? Or did they decide together? Maybe no one said anything at all. If they had hoped their nine children they had together would just accept that their oldest sister Elizabeth was Peter’s biological daughter, then that was the best case scenario. And maybe no one would challenge it. The story never spoken out loud was silently assumed and because of that, the next generation verbalized those assumptions to the younger generations. In that environment, assumptions melted into facts with no real proof. But who would look for evidence? Why would they challenge what was a family “fact”?

What’s the harm? Why not just say you were a widow and then remarried? I would think it would be less of a shock to the community to be a widow over a divorcee. Over 110 years have passed and the questions won’t have answers, just theories. Family stories could point us in a direction, but records would give us a more solid and reliable history. But even records aren’t infallible. People make errors—misspellings, inaccuracies in dates and locations, and flat out provide wrong information.

Because, let’s face it, you could make up a lot more things back then to be “fact” and never have to prove it. Our ancestors would be flabbergasted at the kind of information technology and fact checking resources we have today. Then again, anyone can put anything on the internet. I mean, maybe I’m making up this whole family history debacle because I have some geeky genealogy agenda to deploy on unsuspecting masses. Well, that would be a pretty lame strategy. Plus I’m not that cool. Back to Michael J.

So my next step was to find out what I could about Michael’s short 28 years of life.

…check out Part II

Don’t miss the next Get a Clue post.

Subscribe to my newsletter and get the latest article, practical

genie research hacks, updates about my book The Record Keeper, and more!

0